History of Mapping

Reading time

Content

We have already learned a definition of what a map is. But how do we distinguish a map from a plan or a sketch, or a simple drawing? That is a rather philosophical question. What is known is that people used to draw maps (or plans, geographical sketches, …) long before the word “map” was even introduced. One of these oldest relics which we may call a map, is an engraving on a Mammoth tusk – a plan of meanders of river Thaya in the south Moravia, also depicting a camp of the indigenous people. This engraving probably dates at least 20 000 years into history.

Mammoth tusk engraving map, Petr Novák, Wikipedia

One notable example of a very old map (or “map”), is the so-called Mappa di Bedolina – one of the earliest maps, which survived till the current era. As with other very old maps, it is hard to tell its actual age, due to its unknown date of origin. It is believed that it was created around 1000 BCE. Mappa di Bedolina is a 4 metres length plan of the valley around Bedolina, Lombardy. Another example of a map this old is a city plan of Babylonian city Nippur.

Mappa di Bedolina, Luca Giarelli / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Map of the Babylonian city of Nippur. Source

If the aforementioned old maps had a scale, we could call them all large-scale or middle-scale maps – they only covered a small piece of the Earth’s surface. That is due to the fact that the area known to their authors was quite limited. Since then, as the human population grew and the ancient civilizations expanded, maps covering larger areas have appeared. As a result of the continuous discovery of the Earth by these civilizations, first maps of the known world were created.

Notable is the Anaximandros’ map of the world. The actual map was not preserved to the current times, but it is known that its shape and design affected many maps created afterwards. We call them “round maps”, as they have a circular shape.

Anaximander world map. Probable reconstruction.

One of these maps, which survived until the current era, is the Hereford Mappa Mundi map, created around 1280. It depicts known continents – Europe, Asia and Africa. It has Jerusalem in the centre of the map and it is oriented such that east is on the top of the map and north is on the left side. The Hereford Mappa Mundi depicts locations from Ganges river in the east to the Strait of Gibraltar to the west and from the Baltic sea in the north to the River Nile in the south.

Hereford Mappa Mundi.

The eastern orientation of the old “world” maps was typical, due to the east was considered the direction to heaven. The northern orientation of maps, which is common nowadays, emerged later. Mediaeval maps called Portolan charts were using the northern orientation. These maps were produced from the 13th century onward. Their purpose was for nautical navigation. They are known for their precise depiction of coastlines and for the fact that loxodromes (rhumb lines) are displayed as straight lines on the map. Oldest known of these Portolan charts is Carta Pisana.

Carta Pisana. The preserved piece.

In the late 15th century, Martin Beheim created his globus, a spherical depiction of the earth surface. It was not the first globus ever created, it is known that globes existed in the antique times, but the globe by Martin Beheim is the oldest one which was preserved until today.

“Erdapfel” – the globe of Martin Beheim. Source

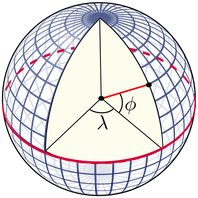

In the 16th century, cartography was significantly influenced by the mathematician Gerhard Mercator. Mercator created a number of maps, globes and atlases. He is also considered the author of the word “atlas” in the cartographic meaning – a collection of maps sharing a similar composition and reflecting a certain shared theme or describing a certain region. Gerhard Mercator has also set base for the field of mathematical cartography (more on mathematical cartography in the chapter “Map Projections and Coordinate Systems”).

Further developments in mapping were vastly affected by the invention of letterpress printing and the expansion of printing techniques. Printing made the reproduction of maps significantly easier. Prior to that, maps were manually redrawn, piece by piece, making every map de facto original.

Maps gained better precision through the centuries as the measuring techniques improved and the understanding of the Earth’s shape and size evolved. In the 16th century first measurements of the Earth’s meridian (called an “arc measurement”) were done in France – a technique of counting the revolutions of a spinning wheel of a carriage was used to measure the distance from Paris to Amiens. The circumference of the whole meridian (and the Earth) was then calculated. The invention of the telescope in the 17th century allowed surveyors to precisely measure angles between distant objects and the technique called triangulation made it possible to calculate distances between distant objects. The “arc measurements” were later repeated in the 18th century with more modern measuring devices and leveraging the triangulation technique in Ecuador/Peru and Lapland, further improving the calculation of the Earth’s circumference.

In 1791 metre was officially defined as a base unit for measures of distances, which also helped to improve the precision of maps. During the 18th century Josef Liesgang made significant trigonometric measurements with a proper stabilisation of geodetic points. His measurement of a meridian arc stretched from Moravia (Czechia) to Croatia.

First road atlas, called Britannia Atlas, was created by John Ogilby in the 17th century.

John Ogilby’s Britannia Atlas. Road from London to Bristol.

First map with isolines was created by Edmond Halley. Isolines are lines which connect places with the same value of a certain phenomenon. Halley’s map was depicting a magnetic variation. The method of isolines then gained popularity. Alexander von Humboldt used the isolines to show places with the equal temperate, thus creating a first map with isotherms. Phillipe Buache then made a map of France on which contours were first used – isolines connecting places with equal height. Before Buache’s innovation, the height on maps was shown with a simple method of “hills” or “forests” or the slope was illustrated with hatching.

Edmond Halley's New and Correct Chart Shewing the Variations of the Compass

Another significant development which affected the cartographic works, was the invention of coloured print in the 18th century.

Notable colourful map is a geological map of Britain by William Smith from 1851. Geological maps were created before, but this one is the basis for nowadays geological maps.

William Smith’s geological map. Source

Pierre Charles Francois Dupin is the author of the first modern statistical map. It depicts education and literacy in France and was published in 1826. The method used by Dupin, colourizing regions with a different tint of colour based on a relative value, is known as a choropleth map. Dupin then created more statistical maps of France for other socio-economic phenomena, while using other methods of thematic cartography like graduated symbols.

Statistical (choropleth) map by Pierre Charles Francois Dupin. Source

Several years later, in 1854, John Snow created his famous dot map. This map shows cholera cases during the disease outbreak in London as individual dots. When created, it helped localise poisoned wells and even uncovers the spatial relation between water wells and cases of disease. That cholera event and the work done by John Snow are considered the basics of epidemiology.

John Snow’s map from “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera”.

An innovative approach in creating thematic maps was introduced by Charles Joseph Minard in 1869. He portrayed Napoleon’s march against Russia as a single line changing its thickness. The thickness represents the number of soldiers in Napoleon’s army in a given place and time. This type of map was later called a flow map and Minard’s map was one of the first.

Charles Minard’s chart of Napoleon’s campaign against Russia in 1812.

From the mid 18th to the mid 19th century, many cadastral maps were produced in Europe. These detailed maps of land were often based on very precise geodetic measurements, notably in Austria-Hungary. Along with the cadastral maps, detailed maps for military purposes were also produced.